Finding yourself confused by the seemingly endless promotion of weight-loss strategies and diet plans? In this series, we take a look at some popular diets—and review the research behind them.

What is it?

The ketogenic or “keto” diet is a low-carbohydrate, fat-rich eating plan that has been used for centuries to treat specific medical conditions. In the 19th century, the ketogenic diet was commonly used to help control diabetes. In 1920 it was introduced as an effective treatment for epilepsy in children in whom medication was ineffective. The ketogenic diet has also been tested and used in closely monitored settings for cancer, diabetes, polycystic ovary syndrome, and Alzheimer’s disease.

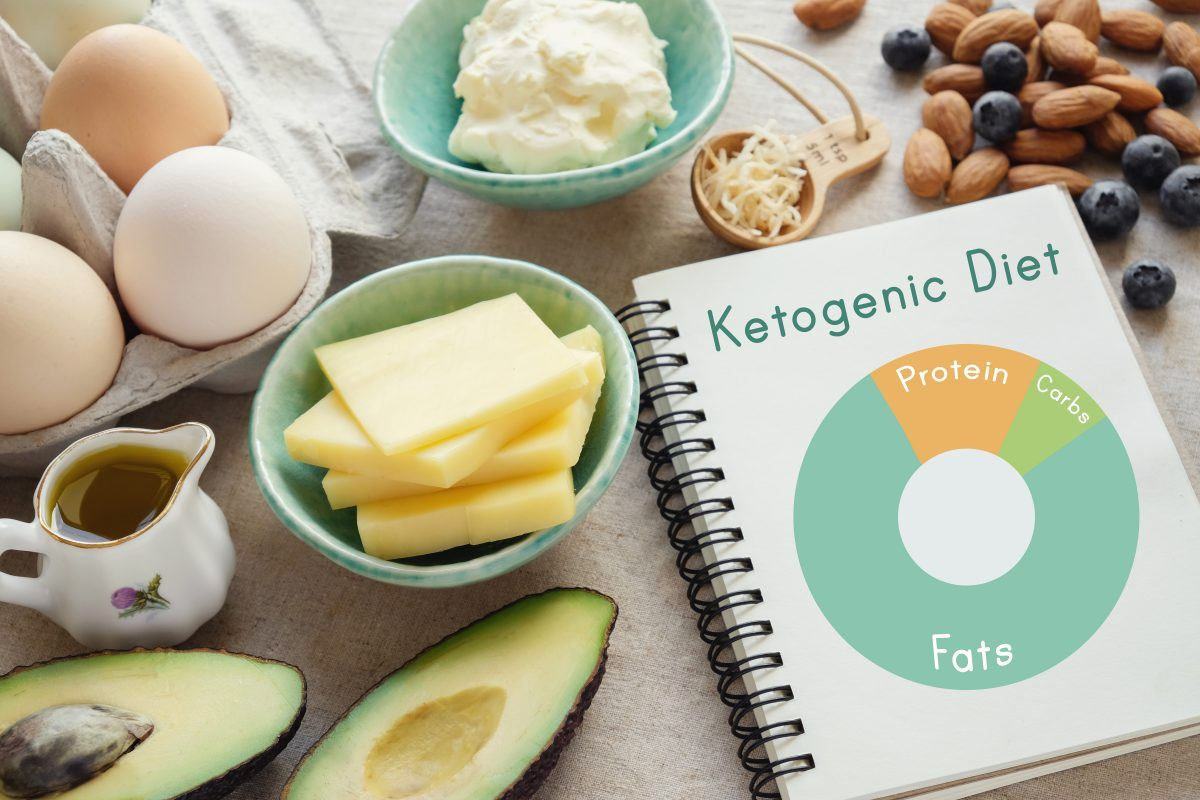

However, this diet is gaining considerable attention as a potential weight-loss strategy due to the low-carb diet craze, which started in the 1970s with the Atkins diet (a very low-carbohydrate, high-protein diet, which was a commercial success and popularized low-carb diets to a new level). Today, other low-carb diets including the Paleo, South Beach, and Dukan diets are all high in protein but moderate in fat. In contrast, the ketogenic diet is distinctive for its exceptionally high-fat content, typically 70% to 80%, though with only a moderate intake of protein.

How It Works

The premise of the ketogenic diet for weight loss is that if you deprive the body of glucose—the main source of energy for all cells in the body, which is obtained by eating carbohydrate foods—an alternative fuel called ketones is produced from stored fat (thus, the term “keto”-genic). The brain demands the most glucose in a steady supply, about 120 grams daily, because it cannot store glucose. During fasting, or when very little carbohydrate is eaten, the body first pulls stored glucose from the liver and temporarily breaks down muscle to release glucose. If this continues for 3-4 days and stored glucose is fully depleted, blood levels of a hormone called insulin decrease, and the body begins to use fat as its primary fuel. The liver produces ketone bodies from fat, which can be used in the absence of glucose. [1]

When ketone bodies accumulate in the blood, this is called ketosis. Healthy individuals naturally experience mild ketosis during periods of fasting (e.g., sleeping overnight) and very strenuous exercise. Proponents of the ketogenic diet state that if the diet is carefully followed, blood levels of ketones should not reach a harmful level (known as “ketoacidosis”) as the brain will use ketones for fuel, and healthy individuals will typically produce enough insulin to prevent excessive ketones from forming. [2] How soon ketosis happens and the number of ketone bodies that accumulate in the blood is variable from person to person and depends on factors such as body fat percentage and resting metabolic rate. [3]

Excessive

ketone bodies can produce a dangerously toxic level of acid in the blood, called

ketoacidosis. During

ketoacidosis, the kidneys begin to excrete

ketone bodies along with body water in the urine, causing some fluid-related weight loss.

Ketoacidosis most often occurs in individuals with type 1 diabetes because they do not produce insulin, a hormone that prevents the overproduction of ketones. However in a few rare cases,

ketoacidosis has been reported to occur in nondiabetic individuals following a prolonged very low carbohydrate diet. [4,5]

The Diet

There is not one “standard” ketogenic diet with a specific ratio of macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein, fat). The ketogenic diet typically reduces total carbohydrate intake to less than 50 grams a day—less than the amount found in a medium plain bagel—and can be as low as 20 grams a day. Generally, popular ketogenic resources suggest an average of 70-80% fat from total daily calories, 5-10% carbohydrate, and 10-20% protein. For a 2000-calorie diet, this translates to about 165 grams fat, 40 grams carbohydrate, and 75 grams protein. The protein amount on the ketogenic diet is kept moderate in comparison with other low-carb high-protein diets, because eating too much protein can prevent ketosis. The amino acids in protein can be converted to glucose, so a ketogenic diet specifies enough protein to preserve lean body mass including muscle, but that will still cause ketosis.

Many versions of ketogenic diets exist, but all ban carb-rich foods. Some of these foods may be obvious: starches from both refined and whole grains like breads, cereals, pasta, rice, and cookies; potatoes, corn, and other starchy vegetables; and fruit juices. Some that may not be so obvious are beans, legumes, and most fruits. Most ketogenic plans allow foods high in saturated fat, such as fatty cuts of meat, processed meats, lard, and butter, as well as sources of unsaturated fats, such as nuts, seeds, avocados, plant oils, and oily fish. Depending on your source of information, ketogenic food lists may vary and even conflict.

The following is a summary of foods generally permitted on the diet:

Allowed

- Strong emphasis on fats at each meal and snack to meet the high-fat requirement. Cocoa butter, lard, poultry fat, and most plant fats (olive, palm, coconut oil) are allowed, as well as foods high in fat, such as avocado, coconut meat, certain nuts (macadamia, walnuts, almonds, pecans), and seeds (sunflower, pumpkin, sesame, hemp, flax).

- Some dairy foods may be allowed. Although dairy can be a significant source of fat, some are high in natural lactose sugar such as cream, ice cream, and full-fat milk so they are restricted. However, butter and hard cheeses may be allowed because of the lower lactose content.

- Protein stays moderate. Programs often suggest grass-fed beef (not grain-fed) and free-range poultry that offer slightly higher amounts of omega-3 fats, pork, bacon, wild-caught fish, organ meats, eggs, tofu, certain nuts and seeds.

- Most non-starchy vegetables are included: Leafy greens (kale, Swiss chard, collards, spinach, bok choy, lettuces), cauliflower, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, asparagus, bell peppers, onions, garlic, mushrooms, cucumber, celery, summer squashes.

- Certain fruits in small portions like berries. Despite containing carbohydrate, they are lower in “net carbs”* than other fruits.

- Other: Dark chocolate (90% or higher cocoa solids), cocoa powder, unsweetened coffee and tea, unsweetened vinegars and mustards, herbs, and spices.

Not Allowed

- All whole and refined grains and flour products, added and natural sugars in food and beverages, starchy vegetables like potatoes, corn, and winter squash.

- Fruits other than from the allowed list, unless factored into designated carbohydrate restriction. All fruit juices.

- Legumes including beans, lentils, and peanuts.

- Although some programs allow small amounts of hard liquor or low carbohydrate wines and beers, most restrict full carbohydrate wines and beer, and drinks with added sweeteners (cocktails, mixers with syrups and juice, flavored alcohols).

*What Are Net Carbs?

“Net carbs” and “impact carbs” are familiar phrases in ketogenic diets as well as diabetic diets. They are unregulated interchangeable terms invented by food manufacturers as a marketing strategy, appearing on some food labels to claim that the product contains less “usable” carbohydrate than is listed. [6] Net carbs or impact carbs are the amount of carbohydrate that are directly absorbed by the body and contribute calories. They are calculated by subtracting the amount of indigestible carbohydrates from the total carbohydrate amount. Indigestible (unabsorbed) carbohydrates include insoluble fibers from whole grains, fruits, and vegetables; and sugar alcohols, such as mannitol, sorbitol, and xylitol commonly used in sugar-free diabetic food products. However, these calculations are not an exact or reliable science because the effect of sugar alcohols on absorption and blood sugar can vary. Some sugar alcohols may still contribute calories and raise blood sugar. The total calorie level also does not change despite the amount of net carbs, which is an important factor with weight loss. There is debate even within the ketogenic diet community about the value of using net carbs.

Programs suggest following a ketogenic diet until the desired amount of weight is lost. When this is achieved, to prevent weight regain one may follow the diet for a few days a week or a few weeks each month, interchanged with other days allowing a higher carbohydrate intake.

The Research So Far

The ketogenic diet has been shown to produce beneficial metabolic changes in the short-term. Along with weight loss, health parameters associated with carrying excess weight have improved, such as insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and elevated cholesterol and triglycerides. [2,7] There is also growing interest in the use of low-carbohydrate diets, including the ketogenic diet, for type 2 diabetes. Several theories exist as to why the ketogenic diet promotes weight loss, though they have not been consistently shown in research: [2,8,9]

- A satiating effect with decreased food cravings due to the high-fat content of the diet.

- A decrease in appetite-stimulating hormones, such as insulin and ghrelin, when eating restricted amounts of carbohydrate.

- A direct hunger-reducing role of ketone bodies—the body’s main fuel source on the diet.

- Increased calorie expenditure due to the metabolic effects of converting fat and protein to glucose.

- Promotion of fat loss versus lean body mass, partly due to decreased insulin levels.

The following is a summary of research findings:

The findings below have been limited to research specific to the ketogenic diet: the studies listed contain about 70-80% fat, 10-20% protein, and 5-10% carbohydrate. Diets otherwise termed “low carbohydrate” may not include these specific ratios, allowing higher amounts of protein or carbohydrate. Therefore only diets that specified the terms “ketogenic” or “keto,” or followed the macronutrient ratios listed above were included in this list below. In addition, though extensive research exists on the use of the ketogenic diet for other medical conditions, only studies that examined ketogenic diets specific to obesity or overweight were included in this list. (This paragraph was added to provide additional clarity on 5.7.18.)

- A meta-analysis of 13 randomized controlled trials following overweight and obese participants for 1-2 years on either low-fat diets or very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diets found that the ketogenic diet produced a small but significantly greater reduction in weight, triglycerides, and blood pressure, and a greater increase in HDL and LDL cholesterol compared with the low-fat diet at one year. [10] The authors acknowledged the small weight loss difference between the two diets of about 2 pounds, and that compliance to the ketogenic diet declined over time, which may have explained the more significant difference at one year but not at two years (the authors did not provide additional data on this).

- A systematic review of 26 short-term intervention trials (varying from 4-12 weeks) evaluated the appetites of overweight and obese individuals on either a very low calorie (~800 calories daily) or ketogenic diet (no calorie restriction but ≤50 gm carbohydrate daily) using a standardized and validated appetite scale. None of the studies compared the two diets with each other; rather, the participants’ appetites were compared at baseline before starting the diet and at the end. Despite losing a significant amount of weight on both diets, participants reported less hunger and a reduced desire to eat compared with baseline measures. The authors noted the lack of increased hunger despite extreme restrictions of both diets, which they theorized were due to changes in appetite hormones such as ghrelin and leptin, ketone bodies, and increased fat and protein intakes. The authors suggested further studies exploring a threshold of ketone levels needed to suppress appetite; in other words, can a higher amount of carbohydrate be eaten with a milder level of ketosis that might still produce a satiating effect? This could allow inclusion of healthful higher carbohydrate foods like whole grains, legumes, and fruit. [9]

- A study of 39 obese adults placed on a ketogenic very low-calorie diet for 8 weeks found a mean loss of 13% of their starting weight and significant reductions in fat mass, insulin levels, blood pressure, and waist and hip circumferences. Their levels of ghrelin did not increase while they were in ketosis, which contributed to a decreased appetite. However during the 2-week period when they came off the diet, ghrelin levels and urges to eat significantly increased. [11]

- A study of 89 obese adults who were placed on a two-phase diet regimen (6 months of a very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet and 6 months of a reintroduction phase on a normal calorie Mediterranean diet) showed a significant mean 10% weight loss with no weight regain at one year. The ketogenic diet provided about 980 calories with 12% carbohydrate, 36% protein, and 52% fat, while the Mediterranean diet provided about 1800 calories with 58% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 27% fat. Eighty-eight percent of the participants were compliant with the entire regimen. [12] It is noted that the ketogenic diet used in this study was lower in fat and slightly higher in carbohydrate and protein than the average ketogenic diet that provides 70% or greater calories from fat and less than 20% protein.

Potential Pitfalls

Following a very high-fat diet may be challenging to maintain. Possible symptoms of extreme carbohydrate restriction that may last days to weeks include hunger, fatigue, low mood, irritability, constipation, headaches, and brain “fog.” Though these uncomfortable feelings may subside, staying satisfied with the limited variety of foods available and being restricted from otherwise enjoyable foods like a crunchy apple or creamy sweet potato may present new challenges.

Some negative side effects of a long-term ketogenic diet have been suggested, including increased risk of kidney stones and osteoporosis, and increased blood levels of uric acid (a risk factor for gout). Possible nutrient deficiencies may arise if a variety of recommended foods on the ketogenic diet are not included. It is important to not solely focus on eating high-fat foods, but to include a daily variety of the allowed meats, fish, vegetables, fruits, nuts, and seeds to ensure adequate intakes of fiber, B vitamins, and minerals (iron, magnesium, zinc)—nutrients typically found in foods like whole grains that are restricted from the diet. Because whole food groups are excluded, assistance from a registered dietitian may be beneficial in creating a ketogenic diet that minimizes nutrient deficiencies.

Unanswered Questions

- What are the long-term (one year or longer) effects of, and are there any safety issues related to, the ketogenic diet?

- Do the diet’s health benefits extend to higher risk individuals with multiple health conditions and the elderly? For which disease conditions do the benefits of the diet outweigh the risks?

- As fat is the primary energy source, is there a long-term impact on health from consuming different types of fats (saturated vs. unsaturated) included in a ketogenic diet?

- Is the high fat, moderate protein intake on a ketogenic diet safe for disease conditions that interfere with normal protein and fat metabolism, such as kidney and liver diseases?

- Is a ketogenic diet too restrictive for periods of rapid growth or requiring increased nutrients, such as during pregnancy, while breastfeeding, or during childhood/adolescent years?

Bottom Line

Available research on the ketogenic diet for weight loss is still limited. Most of the studies so far have had a small number of participants, were short-term (12 weeks or less), and did not include control groups. A ketogenic diet has been shown to provide short-term benefits in some people including weight loss and improvements in total cholesterol, blood sugar, and blood pressure. However, these effects after one year when compared with the effects of conventional weight loss diets are not significantly different. [10]

Eliminating several food groups and the potential for unpleasant symptoms may make compliance difficult. An emphasis on foods high in saturated fat also counters recommendations from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Heart Association and may have adverse effects on blood LDL cholesterol. However, it is possible to modify the diet to emphasize foods low in saturated fat such as olive oil, avocado, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish.

A ketogenic diet may be an option for some people who have had difficulty losing weight with other methods. The exact ratio of fat, carbohydrate, and protein that is needed to achieve health benefits will vary among individuals due to their genetic makeup and body composition. Therefore, if one chooses to start a ketogenic diet, it is recommended to consult with one’s physician and a dietitian to closely monitor any biochemical changes after starting the regimen, and to create a meal plan that is tailored to one’s existing health conditions and to prevent nutritional deficiencies or other health complications. A dietitian may also provide guidance on reintroducing carbohydrates once weight loss is achieved.

A modified carbohydrate diet following the Healthy Eating Plate model may produce adequate health benefits and weight reduction in the general population. [13]

Related

References

- Paoli A, Rubini A, Volek JS, Grimaldi KA. Beyond weight loss: a review of the therapeutic uses of very-low-carbohydrate (ketogenic) diets. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013 Aug;67(8):789.

- Paoli A. Ketogenic diet for obesity: friend or foe?. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014 Feb 19;11(2):2092-107.

- Gupta L, Khandelwal D, Kalra S, Gupta P, Dutta D, Aggarwal S. Ketogenic diet in endocrine disorders: Current perspectives. J Postgrad Med. 2017 Oct;63(4):242.

- von Geijer L, Ekelund M. Ketoacidosis associated with low-carbohydrate diet in a non-diabetic lactating woman: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015 Dec;9(1):224.

- Shah P, Isley WL. Correspondance: Ketoacidosis during a low-carbohydrate diet. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jan 5;354(1):97-8.

- Marcason W. Question of the month: What do “net carb”, “low carb”, and “impact carb” really mean on food labels?. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Jan 1;104(1):135.

- Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Comparison of effects of long-term low-fat vs high-fat diets on blood lipid levels in overweight or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013 Dec 1;113(12):1640-61.

- Abbasi J. Interest in the Ketogenic Diet Grows for Weight Loss and Type 2 Diabetes. JAMA. 2018 Jan 16;319(3):215-7.

- Gibson AA, Seimon RV, Lee CM, Ayre J, Franklin J, Markovic TP, Caterson ID, Sainsbury A. Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obes Rev. 2015 Jan 1;16(1):64-76.

- Bueno NB, de Melo IS, de Oliveira SL, da Rocha Ataide T. Very-low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet v. low-fat diet for long-term weight loss: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2013 Oct;110(7):1178-87.

- Sumithran P, Prendergast LA, Delbridge E, Purcell K, Shulkes A, Kriketos A, Proietto J. Ketosis and appetite-mediating nutrients and hormones after weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013 Jul;67(7):759.

- Paoli A, Bianco A, Grimaldi KA, Lodi A, Bosco G. Long term successful weight loss with a combination biphasic ketogenic mediterranean diet and mediterranean diet maintenance protocol. Nutrients. 2013 Dec 18;5(12):5205-17.

- Hu T, Mills KT, Yao L, Demanelis K, Eloustaz M, Yancy Jr WS, Kelly TN, He J, Bazzano LA. Effects of low-carbohydrate diets versus low-fat diets on metabolic risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Oct 1;176(suppl_7):S44-54.

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.