Fritz Haber

Although he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the

Fritz Haber’s

The Haber-Bosch Process

In 1905 Haber reached an objective long sought by chemists—that of fixing nitrogen from air. Atmospheric nitrogen, or nitrogen gas, is relatively inert and does not easily react with other chemicals to form new compounds. Using high pressure and a catalyst, Haber was able to directly react nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas to create ammonia.

His process was soon scaled up by BASF’s great chemist and engineer Carl Bosch and became known as the

Background

Haber (

After a few years of moving from job to job, he settled into the Department of Chemical and Fuel Technology at the

In 1911 he was invited to become director of the Institute for Physical Chemistry and Electrochemistry at the new Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft in Berlin, where academic scientists, government, and industry cooperated to promote original research.

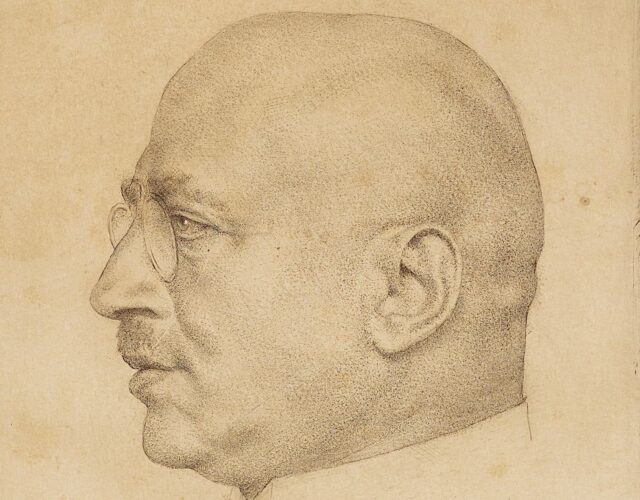

Caricature of Fritz Haber Releasing Gas on a WWI Battlefield, illustration from the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, after 1910–before 1940.

Poison Gas and a Controversial Legacy

The

During the war Haber threw his energies and those of his institute into further support for the German side. He developed a new weapon—poison gas, the first example of which was

His promotion of this frightening weapon precipitated the suicide of his wife, Clara Immerwahr Haber, who was herself a chemist, and many others condemned him for his wartime role. There was great consternation when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1918 for the

After World War I, Haber was remarkably successful in building up his institute, but in 1933 the anti-Jewish decrees of the Nazi regime made his position untenable. He retired a broken man, although at the time of his death he was on his way to investigate a possible senior research position in Rehovot in Palestine (now Israel).

Featured image: Autographed etching of Fritz Haber from the Papers of Georg and Max Bredig, 1922.

Science History Institute